The temperature has risen considerably in the past few days, both across the country as a whole and especially as we have moved northward, leaving us to regret not having taken the time for a trip to Merzouga for a camel trek across the sand dunes of the Sahara. Our brief passage through Marrakesh a few days ago in order to get back on the train line demonstrated the current impracticality of heading to the desert. In the two weeks since our initial landing in Marrakesh, the temperature had risen more than ten degrees to 35oC (95oF). The Sahara would be prohibitively scorching.

We move north to the port city of Tangier to reconnect with Hatim, the Moroccan-Canadian we met on the ferry from Spain. He’d left us his phone number and I called him from a payphone outside a rare internet café near our hostel in Meknes. He has big plans for our final few days in his country.

In meeting Hatim and his girlfriend in Tangier, on their month-long vacation in Morocco, we have been invited to see a view of the country that otherwise would have been out of reach. Hatim began our tour of Tangier by taking us to his Grandmother’s house for a traditional lunch; to a communal bakery where those unable to bake their own bread bring their dough to be baked and returned; to the major sites of Tangier; to an ocean side café or sunset and a host of other places we never would have otherwise found. It is solely because of Hatim that we have seen the real Morocco. It has been incredible.

It is solely because of Hatim that we have seen the real Morocco. It has been incredible.

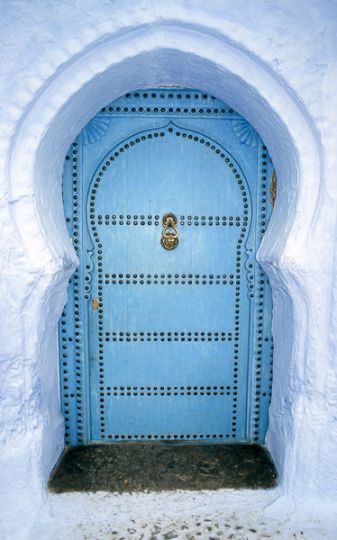

Also on Hatim’s list, for our second day in Tangier, is a rental car and a day trip to Chefchouen, an impossibly picturesque town defined by its mountain setting and iridescent blue hues and drug dealers selling chunks of cannabis the size of house bricks.

We wander, eat and wander some more, until we reach the far end of the town where a river runs under a bridge and over a brief fall. Some of the outflow of the falls is siphoned to the left and right banks, where it is funneled through concrete troughs and into basins, part of a tiny pavilion, with one on each side of the falls. It’s a communal laundry station. Standing in the shade of the roof, local women have stacks of clothes at their feet and take turns working to clean their garments. Each concrete basin also consists of a ridged washboard for heavy scrubbing.

I’ve never seen anything like this, but after a few unwelcome photos, it’s clear the regular folks just doing their laundry do not want us to stick around.

In the winding, narrow streets of Chefchaouen, plenty of shops hawk the usual Morocabilia, but beside a 550 year old mosque, a certain store has our names on it.

Joe and I had thought about carpets. We’ve wanted carpets since we set foot in Marrakesh. But there were just so many options. And when the experience of getting a Coke can be an exhaustive ordeal of haggling, translation, ceremonial mint tea drinking and general time wasteage, the prospect of buying even postage stamp-sized carpets is daunting. We were resigned to pass.

That was until Hatim told us about a place where, last year, he and Cheryl bought 15 for their friends and their apartment in Calgary and had been quite happy. We set out immediately.

Hatim approaches the shop and is instantly recognized by the owner, standing outside. We purposely lag behind while Hatim works his magic before waving us in. Inside a tiny room, packed floor to ceiling with neatly folded carpets, the owner sits at a small desk opposite the weaving loom. It is eerily quiet in the store, the stacks of carpet providing exceptional sound dampening. Hatim tells us we will get Moroccan prices and the owner chimes in that we’re paying “un prix catastrophique.” His selection is enormous.

In striking contrast to Persian or Turkish rugs, Moroccan carpets are much thinner, resembling a thin blanket or a throw. And they are soft. Made by hand on a loom in the store, completing each carpet, measuring about six feet by ten feet, requires a half day’s work. Some have highly intricate, abstract designs in a vast array of colours. Others are more minimal, using only three or four colours and sparse shapes. I browse the stacks and pull out folded carpets based on the few colours I can see, curious as to the designs inside.

The usual tourist prices referred to by backpackers are about $50 US each. But ten minutes after entering the store, with none of the characteristic haggling, Hatim has us out the door with two very nice tapis for $15 apiece.

We’d made the trip to Chefchaouen with Fatima, Hatim’s childhood friend. Her singing of traditional Moroccan songs and stories of growing up with Hatim made for a fun trip. Trying in French to explain to Fatima my colon cancer research, the subject of the Master’s degree I’d just finished, made for a bit of challenge. Fatima told us of Hatim’s birthday the following day, and we were thrilled to take him for lunch in a gorgeous restaurant in Chefchaouen. Hatim had so radically changed our experience in Morocco that we simply couldn’t imagine the tragedy of what would have been our original itinerary. Our 18 days in Morocco have truly been a magic carpet ride.

Hatim had so radically changed our experience in Morocco that we simply couldn’t imagine the tragedy of what would have been our original itinerary. Our 18 days in Morocco have truly been a magic carpet ride.

Bus rides through arid hills and unused scrub lands and farmlands, police checkpoints where the drivers have to pay off the cops to pass, impromptu pickups and drop-offs, rest stop beggars endlessly circulating in the bus isles before departure, desolate shanty towns with crumbling buildings, myriad Coca Cola vendors and mobile phone shops, fetid refuse piles in the town square, loaded-down donkeys wailing in protest — it’s all been an incredible journey of interesting sights, sounds and smells.

But as Rich Western Tourists, are we exploiting a country where, according to UNICEF in 2004, a scant 38% of adult Moroccan women are able to read? Probably, but it doesn’t seem to be generating any resentment. While we’re certainly looked at by countless vendors and “guides” as walking wallets, just as often our bus rides had us as the center of attention, with fellow riders wanting to know where we’re from, what cities we’ve visited, what we’ve enjoyed and where we’re going. And they loved looking at the maps of their towns in our guidebooks, often pointing out interesting locations and points of pride: a beautiful view, a market or their homes. Always friendly, it was even sometimes followed by phone numbers and offers of tours and meals, which, unfortunately, we were never able to do. Moroccans are intensely proud of their country and they love that a couple of white guys in big backpacks are checking it out, too.

Now, my friend, if you’re interested in having a good meal, I have a cousin who has a great restaurant…

Over the past few weeks, a few people have emailed questions about security and the feelings of Moroccans towards Westerners. Is it safe? Do people talk about global politics? Do you try and be inconspicuous? (because two tall, white guys in a backwater Moroccan town of 500 people can just blend right in…)

After parting ways in Tangier with Hatim, Sheryl and Fatima before our ferry back to Europe, a random man who approached us effectively cemented our experiences in Morocco. From a man who didn’t appear particularly worldly or affluent — in fact, he was probably a hustler trying to “guide” us in exchange for a few dollars — we saw the ability to make a distinction that even seems to elude people who view the world through the comparatively sophisticated lens of western life and media. Maybe, however, it eludes them precisely because of the view through that lens.

“Where you from?” he asked us. Germany? Spain? English? “Ah! Canada! Amer-eeka!” he shouted with a broad smile, now visibly happy to be escorting us down the street. “Canada good! Amer-eeka good!” He paused to firmly and genuinely shake both our hands. I was generally surprised, given the current global political climate, at even his initial reaction, but as he continued what shone through was logic that simply is not pervasive in America.

“Amer-eeka people good, but George Boosh bad. Very bad. He craaazy man.” Exasperated at even the thought of Bush, he waved his hands in frustration. But he walked with us with a smile and continued to offer his perspective. Much more than in the United States, people abroad seem to understand and even embrace the distinction between the people of a nation and their government. In the months before the war in Iraq, for example, count the gratuitous French-bashing in one night of Iraq-related news. I didn’t want to bring up Iraq to this man, but he promptly did it for me. “Iraq bad — many people everywhere die. Big mess bad. George Boosh bad but Amer-eekan people welcome in Morocco! One thousand welcomes in my country to you, Amer-eeka and Canada!”

We reached the main street that would bring us to the pizza shop we were seeking. Our escort departed without so much as a hint that we should consider reaching for our wallets. He simply left us with more good wishes and a smile. Precisely how we are about to leave Morocco.