Sir, please, come! It’s the best of the best! Please! Sir! Come and sit! Sir!” Having just finished a massive meal, I’m in no mood to eat. But I’m surrounded by tables piled high with tiers of fresh kabobs of spiced lamb and beef and fish and chicken. Mountains of hot vegetables send their steam into the sky. Cold salads and fruit tumble towards seas of sauces in vibrant red and green and yellow.

Wild, boastful, friendly claims fill the air — every proprietor is our best friend, every stall dishes up the best food in town. Food is everywhere.

Lit by strings of bare light bulbs hanging overhead, powered by hidden but humming generators, tonight the Place Djemaa el-Fna (Square of the Dead) is a bazaar of epic gastronomic proportions. Wild, boastful, friendly claims fill the air — every proprietor is our best friend, every stall dishes up the best food in town. Food is everywhere. The sights and sounds and smells from the arrays of smoking grills and bubbling pots are amazingly rich and complex. Patrons, locals and tourists alike, wander and take it all in, cruising through a surreal galaxy of mouth-watering treasures.

The road to Marrakesh, Morocco, ran through southern Portugal and Spain and although mainland Europe is some 650 km north of here, every step through Djemaa el-Fna has the feel of another world. Thousands of people are on the streets and in the plaza tonight, as we step out of Hotel Ali, just back from the edge of el-Fna. Soot-spewing motorbikes dart through the masses at breakneck speed and at earsplitting volume. If there are traffic lanes, they are mere suggestions. Vendors hawk books and phone cards and trinkets on the sidewalks. “Sir, you need sunglasses, sir!” “20 postcards, one dollar!”

We scramble to avoid the donkey-drawn carriage hurtling through the crowd gathered around a henna tattoo artist. “You should have scorpion! Come, please!” We dodge a tiny, honking taxi careening dangerously close, and we’ve only just left the hotel door.

As we reach the periphery of the plaza itself, smoke wafts over us and we’re engulfed by the smell of succulent beef. And there’s music. A semi-circle of snake charmers play their pungis at top speed for the gathered crowd as the coiled cobras bob and weave before them. Monkeys and lemurs on leashes bounce and run and climb for their minders, collecting coins and depositing them in cans. A small group of drummers pound out a blisteringly fast and precisely coordinated rhythm as a team of teenage dancers, clad all in white, hop and jump and intertwine for another group of spectators. Bells clang and castenettes clatter and other instruments add even more layers to the swirling mix. I long for a video camera.

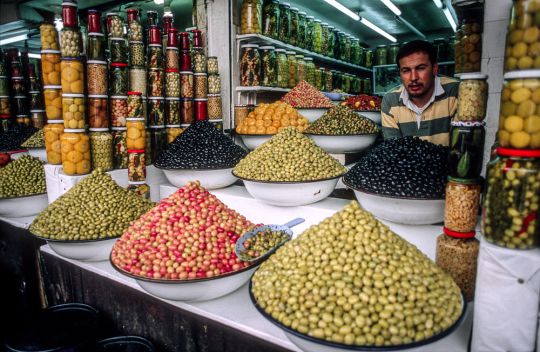

The outer ring of el-Fna’s proprietors is primarily comprised of orange juice vendors. Hundreds of oranges are stacked high beside them and on their carts. Even the briefest of eye contact yields a fresh glass poured in an instant and always with a smile and wave. Tiny generators power their juicers and for 2.5 Dirhams (25 cents) you can drink juice from oranges or grapefruit cut and squeezed in front of you. Interspersed between the juice vendors, other carts are loaded with a dozen varieties of dates and apricots and bananas and assorted dried fruits. For not many more Dirhams than a glass of juice, bags of different varieties of dates can be so shockingly disparate in texture and taste as to barely seem to be the same fruit.

When we finally reach the food section at the center of the plaza, there are literally hundreds of choices. Each proprietor stands at the center of his universe of food. Benches and tables form a square around the cooking facilities and successive tiers of fresh food radiate outward, exerting a culinary gravitational pull all their own.

Empty seats are quickly taken as passers-by are given the hard sell by the marketing team — a group of a half-dozen cookers and cleaners and hangers-on — who tout the caliber of their particular wares, displayed on the French- and Arabic-language menus thrust into the night sky. Polite, funny, wry and evangelistic about their food, they are consummate masters of the sales pitch, with many able to entice prospective customers in multiple languages. Between giving orders to his team in Arabic, we listen in awe as one man makes his pitch to customers in English, French, Spanish, German and Italian.

Fresh, steaming sweet mint tea and chewy bread, a delicious hook and lure, is always on offer but merely the tip of the culinary iceberg. Clearly, my friend, this eatery is the best in the square, says one smartly dressed attendant with a bright smile on his face. You’d be an utter fool to eat next door, my friend! At another setup a few meters away, a familiar refrain: I used to work there, says a welcoming host as he tilts his head and casts suspicious eyes to his right, and it’s garbage. Eat with me, sir, and you’ll eat like a king. Come, sit here, have some tea…

The tea is the lubricant by which all the cogs of el-Fna, and indeed Marrakesh, turn. Freshly brewed in huge kettles with several fistfuls of fresh mint thrown in, the drink is incredibly sweet, intensely minty and insanely delicious. And at shops and barbers and food vendors in Djemaa el-Fna, the tea is always free.

Polite, funny, wry and evangelistic about their food, they are consummate masters of the sales pitch, with many able to entice prospective customers in multiple languages.

A slow, meandering tour of el-Fna’s culinary wares eventually brings us back to the team at booth 117, the most animated and certain of tonight’s array of marketers. We’re won over by both witty self-promotion and sheer selection — a tower of food awaits consumption. We get down to business.

“Small shop, small price!’ There is far more to Marrakesh than just the incredible scenes of food and music in Djemaa el-Fna. The square may be the nexus of the city’s activity, but just a few steps in any direction beyond its perimeter, an entirely different world is every bit as fascinating and mysterious. Radiating outward from el-Fna is one square kilometer of covered, labyrinthine streets and narrow alleys, “souqs,” that feature an unparalleled assemblage of Moroccan art, historical sites, houses, stores and workshops.

Organized by trade, each souq has its own consolidated geographic area, sights, sounds and smells. Navigating between the areas, even with a map, is futile guesswork as there are no signs or obvious landmarks. If familiarity is the best technique, we hone our skills early and often — by getting hopelessly lost then working our way back to the square, only to dive in again.

It all feels more frenetic than chaotic, as if to our Western eyes, unaccustomed to medinas and souqs, in this madness there isn’t madness at all. In fact, according to our guidebook, not much has changed about these souqs in hundreds of years. Walking around is a blur, withastonishing variety densely packed into such a small space. Sellers call out, continually showcasing their goods. Mothers carry crying children. A butcher kills, cleans and packs fresh chickens in front of waiting customers. A yelping donkey barrels through the crowded street, pulling a cart of trash. Tourists snap pictures of their newly bought lamps. Stinking refuse is swept into the street. A man carries two live, occasionally flapping chickens by their legs. Vegetable merchants unload their trays of gleaming tomatoes onto plastic sheets on the ground while kids kick a soccer ball against the opposite wall. It’s all part of a vibrant, dynamic and complex tapestry that is nothing short of extraordinary.

One of the closest souqs to el-Fna, Souq Chouari features woven goods from baskets to placemats and hats. Just beyond, carpet shops fill nearby streets. Some types of general shops are ubiquitous, filled with trinkets, children’s toys, batteries and seemingly random items. Gorgeous leather is everywhere. Spices, soaps and perfumes cloud the air around Soul el Attarine. We delve deeper into the maze and are rewarded with the fascinating sights of blacksmiths — usually children, working very hard — pounding and hammering and welding in Souq Haddadine, where they forge all manners of art from ornate brass sinks to chandeliers to furniture.

Yet for all the incredible scenery, photography in the souqs is a fierce challenge. The act of bringing my camera to my face provokes immediate recoil. Hands are waved, faces are covered, yelling ensues — anything to avoid being captured on film.

Yet for all the incredible scenery, photography in the souqs is a fierce challenge. The act of bringing my camera to my face provokes immediate recoil. Hands are waved, faces are covered, yelling ensues — anything to avoid being captured on film. I resort to totally candid technique, hoping that if I don’t raise my camera to my face to compose a shot, subjects won’t notice I’m taking their picture. Shooting from the hip seems to work, but without a digital camera, I’ll have no idea about my success until long after I return home.

There is so much to explore that it takes us a while to contemplate purchasing anything. Where to begin? What do we need? What do we want? And how much can we fit in our bags? The first and only lesson of the souqs is that haggling is equal part sport and necessity. Offers are made and countered. Friendly jousting mixes with hardball bargaining as items are reshelved and people disengage. A deal falls apart over a few Dirhams, as our bargaining encircles the seller’s profit margin, only to be resurrected when we’re sought out a few hundred feet away and offered the price that was insultingly low only minutes earlier. Enchanted by the process, we catch ourselves nixing almost-complete sales, certain of finding an identical item close-by for just a Dirham or two (ten, twenty cents) cheaper. Shopping is both a befuddling and addicting process.

Marrakesh is amazing. Incredibly inexpensive. Beautiful. Crazy. Different. Frustrating.

While materialistic pursuits consume the majority of our days, Marrakesh is filled with artistic and intellectual heft. In a first for us, we are fascinated by the integral role of Islam as we see the faithful called to prayer five times a day. We see historically important mosques and medersas (Islamic schools), some more than 800 years old. In so many ways, each step through Morocco brings a novel world. Examples of fine, ancient architecture are abundant. And we’re thrilled that this is only the beginning.

Universally, we eat like kings, with meals that fill us to the point of bursting, often for less than $4. And in Marrakesh, $4 is double the price of other cities we plan to visit. We eat often. Always well. After all, haggling builds serious appetite.

In a small restaurant off Djemaa el-Fna, a young Moroccan man at the table beside us says hello. Dressed well, he seems clearly beyond the fiscal means which we’ve observed to date in Marrakesh. Living in France now, he tells us that he has returned home for vacation. His English is good, the result of travel to America. When you’re in a café in Morocco, he says with a wink, try something funny: call out the name Mohammed and count how many men respond. He demonstrates his parlor trick with a sharp, “Hey, Mohammed?!” Five heads turn in our direction. Poking fun at his own culture, he jokes about some of the craziness of Marrakesh and of Morocco as a whole. Then he asks if we know his name. He produces his French identity card. His first name: Mohammed.

It seems impossible, but three very full days have passed. We have only begun to explore Marrakesh, but we must push on. With our revised itinerary from Hatim, who couldn’t have been more correct about the necessity of seeing Marrakesh, we plan to stay in the country for at least two weeks. From here, we’re going further south for a two day hiking trip to summit mountains that scrape the four thousand meter mark.

Then back to the sea and the southern resort town of Agadir.

Mattmoud