There are no smiles here. There are no families with strollers and balloons and ice cream for the kids. There is nobody selling ornamental models of monuments. No souvenir key chains or fold-out postcard sets or coffee mugs or t-shirts. There are no smiles here.

There is horror. There is anguish. There is silence. And death.

Here, about 60 km West of Krakow is the town of Oswiecim (pronounced Osh-ven-sheem) and the largest cemetery in Europe. The rest of the world knows Oswiecim as Auschwitz.

From 27 countries around Europe, about 1.5 million people were murdered here. The setting makes it even more difficult to grapple with the magnitude of the tragedy. Quaint farmhouses and fields and forests roll on to the horizon. Stacks of golden wheat. Seas of green cabbage. On a warm, beautifully cloudless summer day in southern Poland, it is bitter irony that a place so peaceful and with such tranquil beauty could have experienced such impossible horror.

The displays, terrible and touching, in buildings used to house over 2000 prisoners (designed to hold 700), document the insanity.

Originally established in Oswiecim as Polish pre-war army barracks, the largest Nazi concentration camp was converted in 1940 for the Final Solution to the Jewish Problem. The displays, terrible and touching, in buildings used to house over 2000 prisoners (designed to hold 700), document the insanity. Maps detail the scope of victims’ final journeys: from Oslo, Norway, to Rhodes, Greece, they were brought from across the continent, some on journeys over 2000 km. To be murdered.

Efforts to improve efficiency weren’t limited to killings. At Auschwitz, nothing was wasted. Plundered from the victims, darkened rooms display what was taken. Cases full of eyeglasses. Mountains of shoes. Piles of dishes, baby clothes, shoe polish and brushes: all to be used by SS officers and their families. Tons of hair, now gray and light brown, originally intended to be woven back into blankets and uniforms in the wartime textile industry.

A room full of suitcases, labeled with the names and dates of birth of their owners. Each person was allowed 25 kg of luggage for their “relocation.” Documents show how many victims were even sold the very train tickets which would deliver them to their end. Pots and pans, segregated by colour, for preparation of Kosher food. Hair and shaving brushes. Razors. Behind the double rows of tall barbed wire fences, charged with 6000 volts of electricity, it’s all here, in the brown buildings behind the gate.

The gate with the prisoner-forged sign arching above, proclaiming “Arbeit Macht Frei” — work makes you free. The guide points out the upside-down “b” — one of the few indications of heartening, if brief, resistance.

Tours wind solemnly through the displays of prison life and death. The average person selected for labour, and not killed immediately upon arrival, lived three to six months. Some lived a week. The horrific medical experiments. The gratuitous torture. The random executions for offenses so severe as crying. It is a draining six hours. It is a wonder how guides present their myriad stories and anecdotes and statistics day after day after day, recounting grim tales and hearing even more stories from visiting survivors and their families. One recent family, our guide recalls, asked to stop while walking down a hallway lined with prisoner photos. In the early days of the camp’s existence, Nazi photographers documented the prisoners with photos and numbered signs like police document criminals with mugshots. The meticulous documentation ended when the sheer volume of prisoners made the record keeping too timely and expensive. In this hallway lined with photographs, the family stopped our guide because amidst hundreds of pictures, they’d recognized their brother.

But for all the evil of Auschwitz, it is Birkenau (officially known as “KL Auschwitz II”) where things became “efficient.”

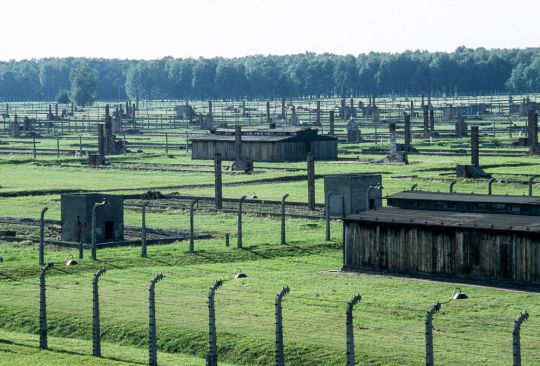

But for all the evil of Auschwitz, it is Birkenau (officially known as “KL Auschwitz II”) where things became “efficient.” A camp of almost 400 acres (10 times the size of Auschwitz I), ruined barracks and towers and fences and train tracks and ovens stretch out on a mind-boggling scale. All in the lush Polish countryside — yet another site of extraordinary beauty visited by the extraordinary horror of war.

A sign on one of the barrack walls notes that those who fail to remember history are bound to live through it again. And some 60 years after the liberation of these terrible places, it is not clear that lessons have truly been learned. Rwanda and Bosnia in the 1990’s. The horror unfolding in Darfour, Sudan, this very summer. While these conflicts do not have equivalent numbers, are the deaths of one million Sudanese people less important than six million Jews? And while Rwanda and Bosnia were eventually and belatedly halted, Darfour rages on, waiting and begging for the world to arrive — tragically late, yet again.

As I walk back from the far corner of the Birkenau camp, where a pond has so many human ashes dumped into it that its water is still gray, I think back to Ryuichi Sakamoto’s moving performance I wrote about from the music festival in Barcelona. The children’s voices he layered into the song were in my head. They were children wholly unaware of politics and history, concerned only with the present and guided by simple clarity of actions.

They asked: “Are we doing the right thing?” If only their clarity could help deliver the right answers.

Poland has so much to see. So beautiful. So many photos. So much amazing food. And friends, too. Paul, who I met in Belgrade, Serbia, on his 16-month, world-spanning extravaganza, joined me in Krakow for bar hopping and the undying pursuit of perogies. And cheap, intra-European airfare rescues me again. With another absurdly inexpensive flight on Wizz Air, I return to Paris.